Refactoring Toward Algorithms in Elixir

Algorithms give a name to a kind of data transformation. They’re the building blocks of programs, and they’re fractal: a program as a whole can be seen as an algorithm, and it’s made up of many smaller algorithms; those algorithms are in turn made up of smaller ones.

Take map, a core concept in functional programming. It takes a collection of things and applies a transformation to each element individually, producing a collection of new things.

Do we really need map, though, when we already have reduce? Why not write:

double = fn int -> int * int end

Enum.reduce(integers, [], fn value, acc ->

# Don't do this in production code 🙃

acc ++ [double.(value)]

end)

While you could of course use reduce in place of every map, we prefer the higher-level map in part because it is much more expressive. It communicates the programmer’s intent much more clearly; any time you see a map, you know it’s going to take a collection and transform each of its individual values in the same way.

This hierarchy of expressiveness exists all throughout the world of algorithms. For instance, Enum.min_by/3 is a reduction—or it could be expressed ad hoc through a series of transformations:

["a", "aa", "aaa", "b", "bbb"]

|> Enum.map(&{&1, String.length(&1)})

|> Enum.min(fn {_, length1}, {_, length2} ->

length1 <= length2

end)

|> elem(0)

# -> "a"

I don’t know anyone who would argue the pipeline version communicates the programmer’s intent clearly here, though.

Descriptiveness versus expressiveness

More broadly, your program can either be a collection of ad hoc algorithms—let’s call them “anonymous” algorithms—or it can be composed of well-known, named algorithms.

Anonymous algorithms are where we all naturally start. When you’re first learning to code, getting a program that does the right thing is sufficient on its own—it doesn’t matter how easy it is to read. But as you grow as a software engineer, you realize it’s much easier to produce “write-only” code that’s impossible to understand later than it is to produce something your coworkers or your future self can understand.

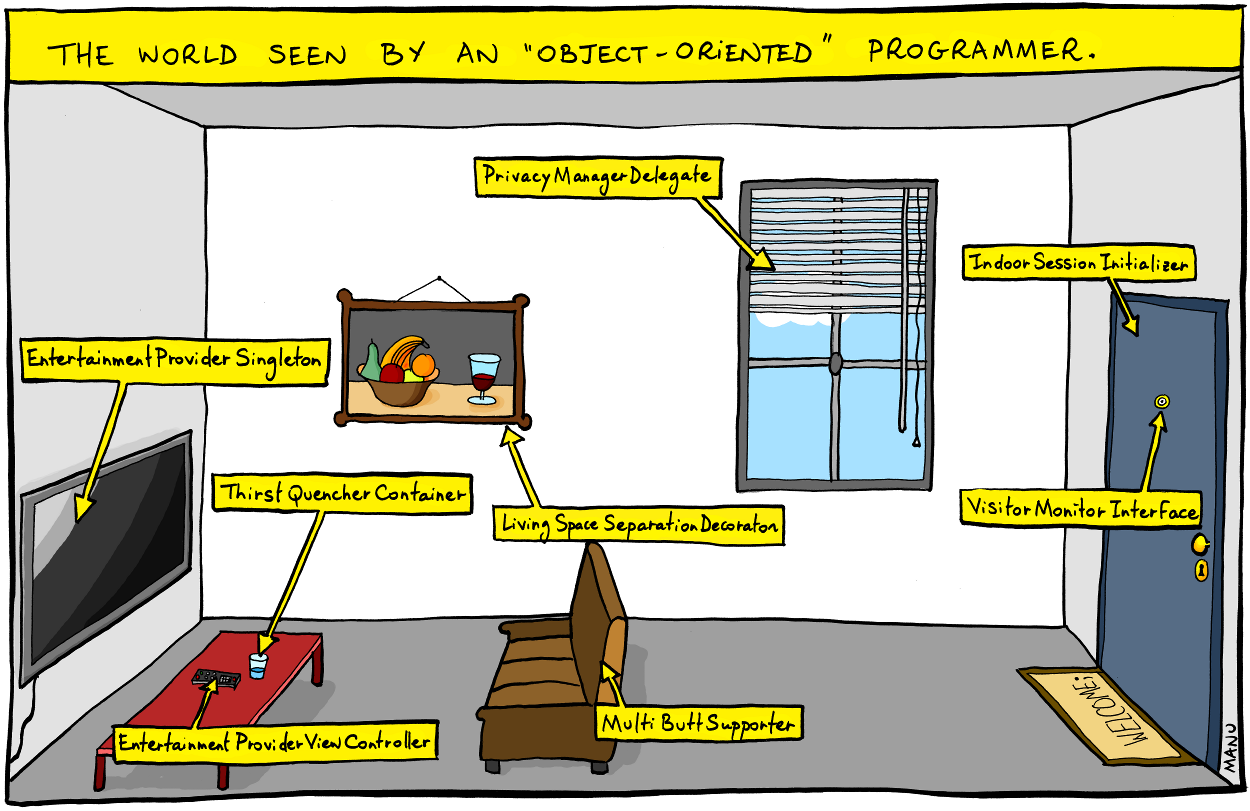

It reminds me of the famous comic about naming:

Image credit: Bonkers World by Manu Cornet

Like the names in the comic, anonymous algorithms are in some ways extremely explicit: in C, each line of a for loop manipulating a global variable tells you exactly what it’s doing… but like the LivingSpaceSeparationDecoration, it manages to be quite specific without being expressive, without capturing the essence of what the thing is.

The fact that a block of code is descriptive does not mean it tells the reader what it really does. So the question is: how do we improve expressiveness?

My answer is to distill my thinking into named algorithms. These provide a shared vocabulary to talk at a high (expressive!) level about what the code is doing.

Let’s look at a few examples where refactoring toward algorithms improves the clarity of code.

Interrogating the code to improve expressiveness

0. A simple example

Suppose you have a collection of user IDs mapped to User structs:

users = %{

123 => %User{

name: "Jane Doe",

email: "jdoe@gmail.com",

prefs: %Preferences{

subscribed_to_emails?: true,

theme: :dark

}

},

456 => %User{

name: "John Doe",

email: "john@doe.com",

prefs: %Preferences{

subscribed_to_emails?: false,

theme: :light

}

}

}

Now suppose you’re given a user ID and you’re asked to unsubscribe that user.

The naive code you might write when you first come to Elixir is an absolute mess:

{_previous_user, updated_users} =

Map.get_and_update(users, user_id, fn user ->

if is_nil(user) do

# user_id did not exist in users; no change.

{nil, nil}

else

updated_prefs = Map.put(user.prefs, :subscribed_to_emails?, false)

{user, %{user | prefs: updated_prefs}}

end

end)

Elixir veterans will recognize that this can be rewritten cleanly with Kernel.put_in/3:

updated_users =

put_in(

users,

[user_id, :prefs, :subscribed_to_emails?],

false

)

This cleanly and succinctly expresses the programmer’s intent, but you first have to know this (somewhat obscure) function exists in the standard library.

1. Replacing recursion with a higher-level construct

Suppose you came across this code in a PR review:

defmodule Ordering do

@doc"""

Reorders the list to guarantee that a given

set of values will always be presented

in the same order.

"""

@spec guarantee_order([integer]) :: [integer]

def guarantee_order(items) do

case order_head(items) do

^items -> items

reordered_head -> guarantee_order(reordered_head)

end

end

defp order_head([e1, e2 | t]) when e1 > e2 do

[e2 | order_head([e1 | t])]

end

defp order_head([e1, e2 | t]) do

[e1 | order_head([e2 | t])]

end

defp order_head(zero_or_one_element) do

zero_or_one_element

end

end

The code clearly spells out what it does—what could be more clear?! (😉)

It’s easy to come into code that looks like this and focus on the mechanics of it—it’s a correct use of recursion, and it will pass every test you throw at it (until you get to performance testing at least). It looks clever! “LGTM,” right?

Until you take a step back. What, exactly, was the ordering criteria here? Oh… this is bubble sort. The whole module can, and should, be replaced with a single call to Enum.sort/1.

In day-to-day programming, it’s hard to go back to working code and ask yourself “is there a named algorithm that could do this same thing?”. It’s even harder to do in code reviews. But it’s important to the long-term maintainability of your codebase.

2. Reordering elements in a list

Suppose you’re writing the classic to-do app and you want to allow users to drag and drop an item in the list to change its priority (its position in the list). A naive implementation might be:

List.pop_at/3to get the item and remove it from the listList.insert_at/3to insert it in the new location

There are a couple subtleties there, though, that could bite you. For instance, if the index you’re popping from comes before the index you’re inserting at, you’ll need to decrement the insertion index. Plus, as your list gets long, doing two passes over the list like this is not ideal.

Now, what happens when your product requirements change and you want to support dragging and dropping any contiguous group of to-dos in the list to reorder them?

The naive approach is to:

- Split your list in three places:

- At the insertion point

- At the start of the “chunk” you’re moving

- At the end of the chunk you’re moving

- Recombine the four resulting pieces into a resulting list

This is extremely messy to read, and the indexing math is easy to get subtly wrong:

defmodule TodoList do

# Bad! Don't use this! 🤪

def slide_chunk(todos, start..last, insert_at_index)

when insert_at_index <= start do

{unchanged_start, after_insertion_pt} = Enum.split(todos, insert_at_index)

# to_slide contains just the elements in the range [start, last]

{to_slide, unchanged_end} = Enum.split(after_insertion_pt, last - insert_at_index + 1)

{new_end_of_slide_range, new_start_of_slide_range} = Enum.split(to_slide, start - insert_at_index)

unchanged_start ++ new_start_of_slide_range ++

new_end_of_slide_range ++ unchanged_end

end

end

(And that’s not even a full implementation, because it doesn’t handle when the insertion index is after the range to be moved!)

The right thing to do here is to use Elixir 1.13’s new Enum.slide/3, which handles those edge cases and saves you from having to get the indexing math. Rather than having this logic in your codebase (or worse, inline in the body of another function!), the named algorithm gives readers a simple, visual metaphor for what you’re doing—sliding a piece of the list elsewhere.

Where to go from here

More than anything, this article is meant to be an exhortation to learn your standard library algorithms and look for opportunities to replace ad hoc transformations with named algorithms.

The challenge in day-to-day development is to:

- Look at your working code using “raw” recursion, reductions, or just a series of transformations and ask “can this be simplified using a named algorithm?”

- If an appropriate algorithm doesn’t spring to mind, figure out the generic term to search for what you need (e.g., you wouldn’t search “how to remove users with empty name field from list in Elixir,” you would search “filter a collection in Elixir”)

- If you still don’t find a good fit, consider extracting out your own algorithm—you won’t get the benefit of it being implemented and tested for you, but at least you’ll improve readability!

Unfortunately there are no shortcuts to learning the standard library. You can make a deliberate study of the algorithms to familiarize yourself with them faster; the Enum flashcards from Elixir Cards are a good choice for this, or you can create your own in a spaced repitition system like Anki.

On the bright side, my experience has been when I’ve had the opportunity to refactor to one of the more obscure algorithms once, that algorithm tends to stick in my head and I see it in more places in the future.

You might get some pushback from coworkers initially. In my experience, algorithms from the standard library are generally accepted as Things the Team Should Know™… but not always. I’ve seen people get flack for even standard library algorithms in code review. In the same way that people coming from imperative programming find a for loop more understandable than map, it will take time to become comfortable with the large body of named algorithms in the standard library. It’s worth it, though, because algorithms are tools for thought; learn them well and you’ll have new tools for higher-level understanding and creation.