02 November 2017

Esoteric Data Structures and Where to Find Them

This is a summary of the CppCon 2017 talk given by Allan Deutsch.

Slot map

- An unordered, associative container similar to hash map

- Assigns items a unique identifier (unlike a hash map, where you provide an identifier)

- Similar to a pool allocator, but with a map-like interface

- Advantages over hash map:

- True constant time lookup, erase, and insert (except when reallocating to grow the size)

- Contiguous storage (for improved traversal/cache lines)

- Reuses memory—if you delete a bunch of items, then insert new ones, it doesn’t result in a bunch of new memory allocations

- Avoids the ABA problem, i.e.,

- You insert an item and receive a key

- You delete the item

- You insert a new item with the same key

- You attempt to access the item pointed to by the old key, but get the new element

- Disadvantages compared to hash maps:

- More memory use, since it dynamically allocates blocks like a vector

- Because it uses contiguous storage, memory addresses of elements are unstable, and lookup is slower than a raw pointer

- Requires a small amount of extra memory

- Potential use cases:

- Storing game entities

- Any place you’d like a map-like interface, but with constant performance and support for as-fast-as-possible iteration

- How it works:

- Array of “slots” (keys we give the user) which indicate each item’s index and the “generation” (the number of times this slot has been used)

- Array of data, which gets pointed to by the slots

- Free list head & tail, indicating which slots should be filled next

- Variants

- No separate index table

- Pros:

- Stable indices/memory addresses

- Lookups only requires 1 indirection, not 2

- Cons:

- Slower iteration (since elements aren’t densely packed)

- Pros:

- Constant size array

- Pros:

- No reallocations (so insert is always constant time)

- Also means no memory usage spikes (where memory usage temporarily doubles as we allocate a new block and transfer the old one over)

- Generations increase roughly uniformly

- No reallocations (so insert is always constant time)

- Cons:

- Dynamic sizing is important for most use cases

- Pros:

- Block allocation

- Pros:

- Constant inserts (like the constant-size array)

- Spikes in memory due to reallocations are smaller

- Iteration speeds are similar to original

- Cons:

- Elements aren’t fully contiguous, so iteration will always be some degree slower

- More cache misses (scales inversely with block size—bigger blocks mitigate this!)

- Adds a third indirection in lookup

- Pros:

- No separate index table

Bloom filters

- A probabilistic, super-duper memory efficient hash “set,” used primarily for short-circuiting otherwise expensive computations

- Find results are only “definitely not” and “maybe”

- Supports find and insert operations only—no actual data elements is stored (since, as the NSA informed us, metadata is not real data! 😉 ), so there’s such thing as a “get” op

- This is especially useful for privacy purposes

- How it works

- On insert, take K (fast) hash functions, each hash function sets one bit in the Bloom filter’s bit field

- On find, hash the object and see if each of the bits you get from your hash functions are set; if they are, the item in question was probably inserted in the past

- Increasing the number of hash functions decreases your false positive probability (but increases the memory usage)

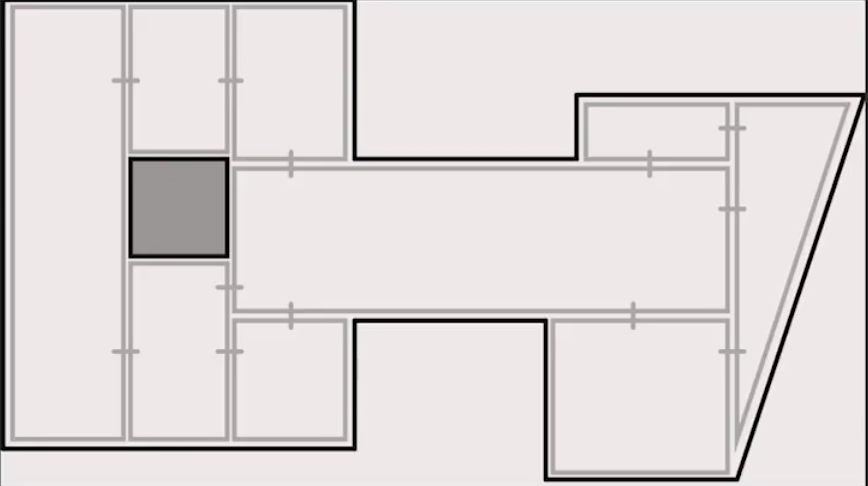

Navigation meshes

- Representation of a search space (used for pathfinding) that reduces the number of nodes necessary to represent the traversable area

- Grid representations suck: They don’t map well onto non-square shapes, and you typically use a lot of them

- Triangle nav meshes improve upon this; using a mix of triangles and squares can improve it even further

- Consider:

- To actually traverse this, you would move from edge to edge to get between nodes, and when you reach your destination node, you could simply beeline to your goal (since you know it will be free of obstacles)

- You can use Recast to create nav meshes, and A* or the like to search them

Hash pointers

- A combination of a pointer and a hash of the thing being pointed to

- Allows you to verify that the data hasn’t been changed since you got the pointer to it

- Most common implementation is in Merkle trees in cryptocurrency blockchains

- Tamper detection: suppose the data in a block has changed maliciously in a blockchain (a series of hash pointers + data). In order for the attacker to “get away with it,” they’ll have to change the data in Block X, plus the hash in Block Y that points to Block X. But, Block Z stored a hashpointer to Block X as well, and its hash included the now-altered hash in Block X, so the attacker has to also change the hash of Block Z (and so on up the chain).

- Verification is O(N), for N number of blocks

- Alternative: Merkle trees

- Tree structure where only the leaves hold data, and all other nodes simply store 2 hash pointers to 2 children

- Verification of the structure takes O(log(N)) time, but that also means it takes less tampering on the part of an attacker